The first to fall was Mita. ‘She’s here. I see her. She’s waiting for me,’ he muttered, collapsing to his knees. I called out to Chen Ming, begging him to help me carry Mita, but he kept glancing back, face twisted in terror, ignoring me. Then he abandoned us, fleeing alone.

I ditched my pack and, with a numb right hand, hoisted Mita’s left shoulder. Dragging him forward was agonizingly slow. ‘Leave me,’ Mita pleaded. ‘We’re not getting out. They’re all here. She’s been watching us.’ I gritted my teeth, ignoring him, pulling him step by step. I shouted for Chen Ming again, hoping he’d stop and fulfill his duty as leader, but then he collapsed too.

‘I can’t go on… They’re coming for me… Please, don’t let them take me. Save me. It’s your fault—I shouldn’t be here. Save me, please…’ he wailed as I passed. I was at my limit, vision blurring, Mita’s weight like a hundred-pound anchor threatening to drag me down.

From afar, Chen Ming’s sobs turned to distorted screams of fear, then choking gurgles. After that, I heard nothing from him. This hellish trek stretched endlessly. The world was silent save for my ragged breaths and Mita’s faint heartbeat. I knew we couldn’t keep going like this—our body heat was fading. Without a windbreak, we’d freeze before night’s end.

But fate wasn’t kind. I tripped, and we both crashed hard. My headlamp flew off somewhere into the fog. In that moment, surrounded by mist, I realized survival was impossible. Mita was alive, barely, his breaths shallow, muttering, ‘Kiyoko, I’m sorry, I’m sorry…’ His mind was slipping. Then I saw them—countless shadows moving around us in the fog. And there, ten meters ahead, stood Kiyoko. Her bloodless skin shimmered with frost, her eyes hollow black voids staring with an otherworldly gaze. Her arms hung limp, twisted unnaturally from frail shoulders, part of her waist missing. Yet her face bore a grotesque smile, lips stretched impossibly wide, fixed on us.

I’d seen hallucinations on mountains before, but none this vivid, none this horrifying. My last memory is Kiyoko lurching toward us, her stiff joints creaking like a marionette. Mita, in my arms, stared at her, exhaled a long breath, and went still. Then my vision went black, and I remember nothing more.

When I awoke, I was at base camp. Another rescue team had found me at the end of M Glacier, they said. Bad weather had stopped them from reaching C2; they’d camped at C1 for nights before turning back. They were shocked to find me there—four kilometers from the U Glacier route. I asked about Mita and Chen Ming. They’d seen only me, nothing else along the way. I stayed at base camp for two weeks, refusing to speak of what happened, no matter who asked.

The weather stayed brutal, halting further ascents, and debate grew about abandoning the rescue. A gnawing dread built in me daily, stronger each time, as if doom loomed. I begged and wept to leave. The head commander, sensing something off about the mountain, declared the mission a failure. We all descended.

The day we left, an unprecedented avalanche struck near base camp. A centuries-old cedar forest collapsed—not even in the avalanche’s path. Some blamed wind pressure, but I know better. This mountain holds forces beyond human grasp, mysterious phenomena ruling everything alive and dead. I’d witnessed them myself. I returned having left four fingers and three toes to that mountain—the price of my survival. Why it spared me, I don’t know. Maybe there’s no reason. Mountain gods defy our understanding.

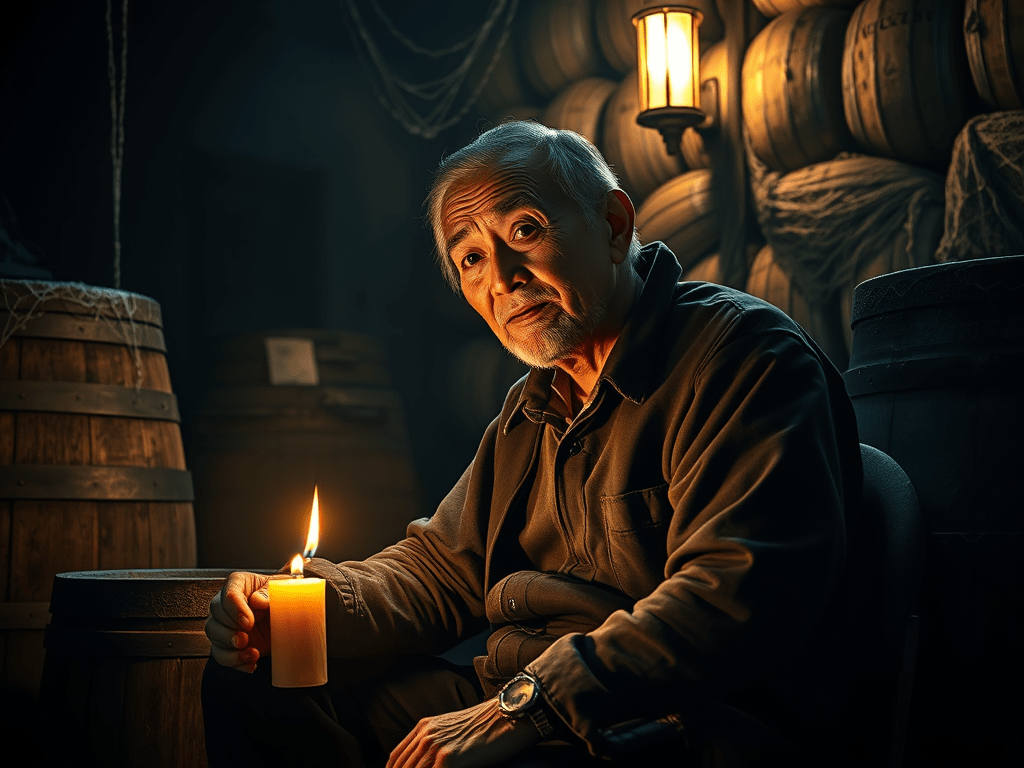

Uncle Ishikawa paused here, slipped off his gloves, and revealed hands with only six fingers remaining. My friend and I held our breath, our faces surely as pale as ghosts. When I asked what happened to Mita, Uncle Ishikawa thought for a moment before replying, ‘I reckon he’s dead… Even if he’s alive, that probably isn’t Mita anymore.’

As we prepared to part ways, he seemed to recall something. ‘Oh, right,’ he said. ‘Did you know the locals avoid naming this mountain directly out of reverence for the gods? They call it Mount Sleepless. It means those who climb it, even after death, can’t rest. They must serve the mountain for seven years, only resting in peace on the eighth.’

After we said goodbye, a shiver ran through me and my friend. Every rustle of wind or grass nearly scared us to death. To shake it off, we ducked into a karaoke bar, singing our lungs out until dawn to bolster our courage. Even then, we felt uneasy, stumbling back to our place only after sunrise. In the end, we agreed on one thing: climbing those snow-covered peaks above 6,000 meters in the death zone is a suicide mission. You couldn’t drag me back there for anything.

Leave a comment