Mountain disasters—those injuries or deaths climbers face—are the grim shadow of mountaineering, stalking every step from the start. They’re harsh but vital lessons: dissecting what went wrong can save lives. Let’s revisit a chilling chapter from Taiwan’s climbing history, the 1971 Qilai group disaster.

In July 1971, as Taiwan’s “Hundred Peaks” were freshly minted, seven top-tier university students formed an all-star team: six men and one woman, hailing from Tsinghua and NTU. This wasn’t just any crew—think mountaineering club president, volleyball captain, badminton champ, and photography head, led by Bo Shengheng, Tsinghua’s mountaineering VP. Their mission?

A multi-day traverse of Qilai’s jagged peaks. Pre-trip weather reports promised clear summer skies, so they launched from Taichung. Day one: a slog to Dayuling. Day two: a hike to Songxue Lodge at Hehuan Mountain. On July 23, they hit the trail—three hours down grassy slopes to Heishuitang, the saddle between Hehuan and Qilai, then up a forested stretch to camp by a dry creek bed. No huts existed then; it was tents or bust.

July 24 was the big push. Fueled by grit, they tackled a grueling 1,000-meter climb to Qilai’s main ridge, setting up camp at 3,000 meters on the sprawling grasslands. The views were epic, the vibe triumphant—everything aligned with their plan. But at midnight on July 25, disaster struck. A ferocious storm—Typhoon Nadine, a sneaky beast that formed mid-climb with no warning—ripped them awake.

Tents shook under howling winds and lashing rain. A crackling radio confirmed the typhoon’s assault, a shock after days of calm forecasts. Anyone who’s faced a mountain storm knows: it’s ten times wilder than flatland weather. Panicked, Bo made a snap call that changed everything: rouse the team, descend 1,000 meters to Heishuitang, then trek three hours back to Songxue Lodge to ride it out.

Picture this: seven soaked students, battling a storm-torn descent. The once-dry creek beds and trails they’d crossed morphed into roaring waterfalls. Drenched, freezing, and spent, they stumbled to Heishuitang after untold torment. Exhausted, they could’ve stopped—rested, warmed up—but Songxue loomed “just” three hours away on a gentle slope. No one suggested regrouping; hypothermia was setting in, morale was mush. They fixated on rescue: if someone could reach the lodge, help would come. So, they pressed on, legs like lead.

That grassy path—normally a breezy stroll—became a death march. Driven by desperation, they scattered, sprinting through the tempest, burning their last reserves. Some ditched backpacks, the “second life” of any climber, to lighten the load. Bo and two others lagged and vanished. Four pushed within 50 meters of Songxue— agonizingly close—when three collapsed. Only Shi Nengjian staggered to the lodge, gasping for aid. Rescuers raced back, reviving Lai, the lone woman, but two were already gone, claimed by the cold. The next day, search teams found the missing three—icy corpses dotting the trail.

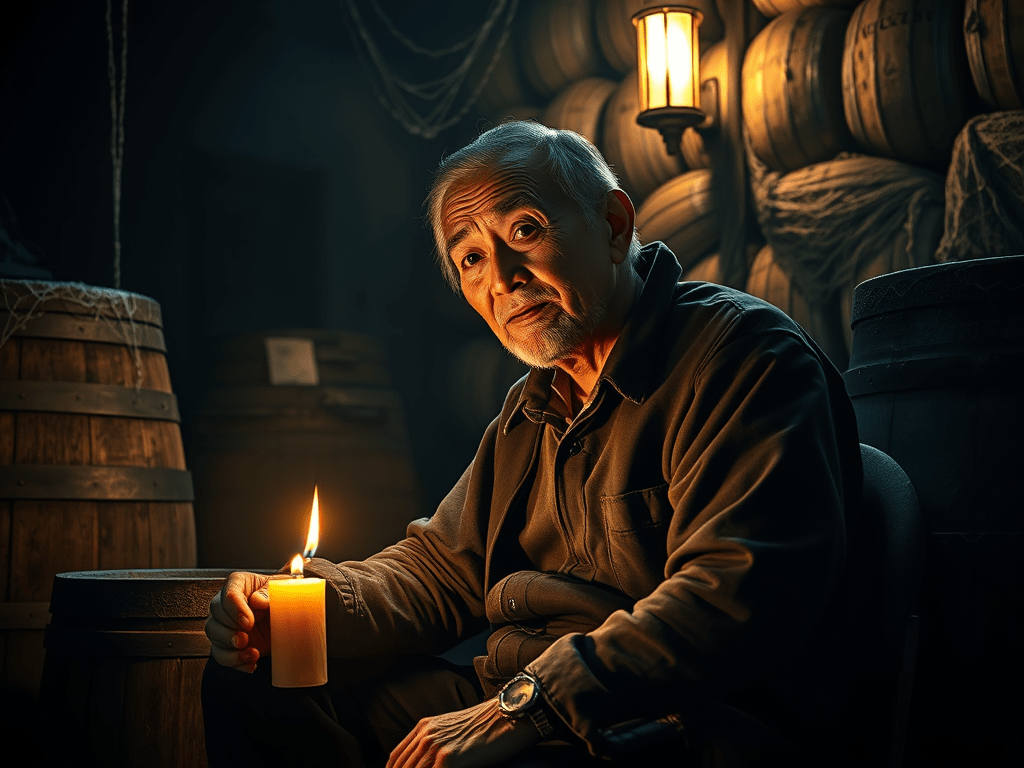

A rescuer I once met called that descent a “corpse pickup.” One image stuck: a body, still strapped to a heavy pack, crouched like a toppled stump, frozen mid-struggle, strength sapped forever. Five deaths—nearly the whole team—stunned 1971 Taiwan. Qilai’s “Black” moniker took root, cemented by this and later disasters, including two bizarre group deaths. It marked an era when climbing passion outran prep and know-how, a brutal wake-up call.

To honor the five Tsinghua students who perished, the university built Qilai Second Fort—a metal refuge hut on the mountain. Initially, it served a grim purpose: a temporary resting place for the victims’ bodies during recovery. That macabre start birthed a haunted reputation. One eerie tale stands out: a climbing team, seeking shelter from rain, bunked at the fort. In the dead of night, knocks rattled the door.

They opened it to find another group of climbers—silent, heads down, sorting gear. No greetings, no chatter. By morning, the visitors were gone, vanished without a sound. Curious, the team glanced at a photo on the wall—five faces, the Tsinghua victims. The silent guests? Their spitting image. Goosebumps guaranteed.

The mountain wasn’t done. On August 8, 1976, tragedy struck again. Eight Army Academy students tackled Qilai when Typhoon Billie roared in. Forced to retreat, one, surnamed Li, was injured and too weak to continue.

They tucked him into a cave for shelter, while the other seven descended for help. Exhaustion splintered the group—some lagged, others pressed on. Only one reached Songxue Lodge to raise the alarm. Rescue came too late: four froze on the trail, two survived, and Li, left waiting, was found dead—curled in a squat, rigid from the cold.

Li’s father enlisted Lin Liangquan, vice-chair of Taichung’s seasoned Mountaineering Association, to search. Lin’s recounting chills to the bone: the night they found Li’s body, he saw the boy’s spirit standing outside their camp, a spectral figure in the dark. A hardened climber, Lin admitted it shook his skepticism—proof, he felt, of “another world.”

Leave a comment