Now, back to Third Company—aka Jingcheng Company, the toughest unit in our little riverside camp. I had a buddy there, a “brother” from two batches ahead of me.

We called him Betel Nut Brother ‘cause he was always chewing betel nut, that classic Taiwanese pick-me-up. He was a solid guy—dependable, rarely screwed up, and looked out for us newbies. At 176 cm and 80-something kilos, he was built like a tank, a real Rambo type.

Then, out of nowhere, he botched everything. Dark circles ringed his eyes, and he shuffled around like he’d collapse any second. We asked what was wrong—he clammed up.

Weirder still, he avoided the dorm. After 9:50 p.m. roll call, he’d be the last one in, lingering indoors but never stepping outside or settling into his bunk.

He was fine on gate duty—three of us plus the White Head squad nearby, eight guards total in a 20-meter radius. No issues there. But when he pulled a shift at the oil depot? That’s when it hit the fan.

The patrol officer found him curled up in a corner of the sentry post, trembling. They hauled him in for questioning the next day—nothing coherent came out. In less than a week, he’d shrunk, gaunt and hollowed out. His paid leave got docked, and finally, he cracked.

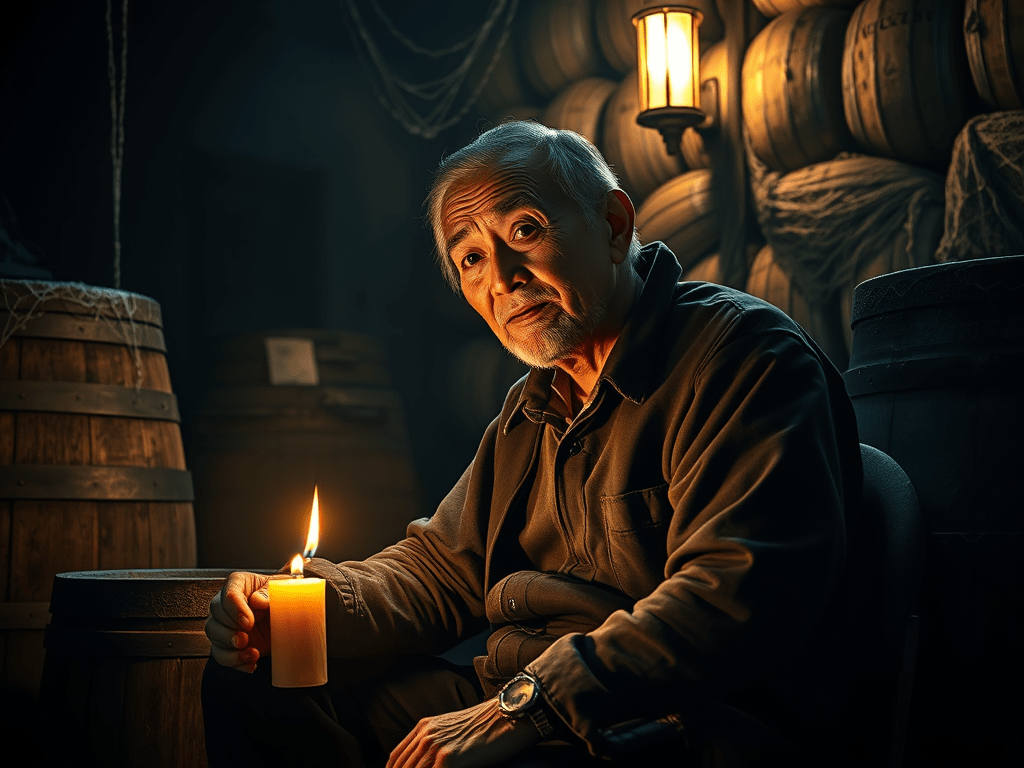

“Every night, I get pressed,” he said. “At the oil depot, twenty-something figures were staring at me. I’d get pressed in my sleep—cursing didn’t help. Open my eyes, and there’d be more: Japanese soldiers, military police, civilians, all watching.”

The two seniors soilders bunking next to him said he’d twitch in his sleep. They figured he was just “taking care of his business” and ignored it. Our indigenous sergeant handed him a Bible, told him to sleep with it on his chest.

“If that fails, use your cap—the national emblem might work.” Betel Nut Brother tried both. No dice. That night, his bunkmates swapped beds with someone else.

Our dorm housed 80-plus guys, and every couple of weeks, someone got “pressed”—that suffocating feeling like a ghost’s sitting on you. The vets swore a good curse would shake it off, and sure enough, you’d hear a muffled “F*** off” in the night.

Next day, someone’d admit they’d been pressed, and the senior vets would slip them a two-hour pass to “go calm their nerves” off-base. Routine stuff.

But Betel Nut Brother’s case was different. They let him sleep by the duty officer’s desk one night, Bible and all.

Morning came—he’d been pressed again. They took him off-base to “collect his spirit,” some traditional ritual. Didn’t work. That night, he lost it—thrashing around the dorm, screaming.

Ten-plus guys, all Rambo-grade like him, couldn’t pin him down. A few got banged up in the chaos. I was on sentry duty, just hearing the commotion from afar. By the time my shift ended, it was quiet—only the Company flag was out, a sign something big had gone down.

Next morning, Betel Nut Brother looked like death—pale, muttering about being pressed again. Then he passed out. The night before had been such a mess that even the company commander got wind of it.

The camp counselor, a stubborn skeptic, called for the ambulance to ship him to Beitou’s 818 Military Hospital—infamous for psych cases. The commander stopped it, though. Instead, a senior drove him and the deputy counselor off-base again.

That afternoon, our gate duty got handed to the camp HQ crew. The whole company—everyone—was confined to the rec room. No one stood watch in our little camp. Whatever was happening outside, only a select few knew, and they weren’t talking. Ask, and you’d get barked at. Betel Nut Brother didn’t come back that day.

Ten days later, he returned—just in time for New Year’s prep. He was himself again, the old cheerful Betel Nut Brother everyone loved. We were doing a big cleanup when someone accidentally pried up a piece of the dorm’s terrazzo floor.

Charms—black, yellow, red—mostly under the window-side bunks. I slept in that row, but my slab was clean, thank God. Were they wards? Curses? No one knew, but it freaked us out enough to keep quiet about it. With our own sweeping done, we got roped into helping the military police downstairs.

Our little camp sat kitty-corner to the main HQ, with the military police right across from it. They had three buildings; we bunked on the third floor of their third one.

Our base was mostly motor pools and oil depots—three-quarters of it, anyway—so aside from a couple of tiny storerooms, we had no space of our own. Living with the MPs wasn’t bad, though. We were Jingcheng Company, the tough nuts, and they were the MPs—riot drills were a blast, decked out in gear, going at each other for real.

Next day, I got assigned to sweep their switchboard room. Jackpot—I ran into Ark, an old buddy from my high school days. Accounting major, mahjong shark, and zero interest in brooms.

He pawned the work off on his junior, and we kicked back with smokes, snacks, betel nut, the works. “Your unit’s been tangled in some dark stuff lately,” he said, nodding at our lockdown day.

I spilled about Betel Nut Brother; he’d only caught a glimpse of our company doing some ritual that day. “No clue what it was,” he shrugged, “but this third building? It’s not clean.”

First floor was fine, he said. Second was dicey. Third—our floor? Unknown.

His boss, a grizzled 40-something sergeant with a voice like gravel, rolled in. Didn’t care we were slacking—brought us food instead. Based on his story, it turns out, the third building used to be an intelligence HQ jail—our dorm was a gutted cell block from the ‘50s, built on Japanese-era bones.

Being local, I did—vague rumors of bad juju. “Early days,” he went on, “the senior-junior system was brutal. Some guys couldn’t hack it—ended themselves. I got thrashed by my senior on this building’s roof just for ranking up faster.”

Lucky for me, a unit reshuffle got me out five months in—off to a saner post. But what happened that lockdown day? Took a month and a boozy night with a freshly discharged junior to find out.

Betel Nut’s spiral started at the oil depot sentry post. One night, nature called, and he didn’t bother finding a bush—just pissed right on the wall outside the shack. That’s when the “pressing” began—night after night, crushed by unseen weight, watched by Japanese soldiers, MPs, and civilians.

The sentry post used to be wooden, replaced with concrete less than two years back. New foundation meant digging, but nothing odd turned up then—or so they thought. During the lockdown, a shaman got involved, puzzled by the spot. An officer who’d served in Penghu piped up about bases built over ancient battlefields, hinting at what might lie beneath.

They dug. Not with machines—shovels and hands, slanting down 80 centimeters under the post’s foundation, deeper than the original 60 cm.

What they found? A clay urn, 60 cm wide, 90 cm tall.

Inside: the bones of a Japanese naval officer. His cap was rotted, but the chrysanthemum badge of the Imperial Navy still gleamed. A brittle paper listed his honors in Japanese—died in a forced landing, a war hero lost to time.

That urn explained everything—Betel Nut’s haunting, the dorm’s restless nights, maybe even those talismans. The ritual that day? Likely to appease whatever spirit he’d pissed off—literally. He came back after ten days in the hospital, his old self again, just as we uncovered those floor charms.

Coincidence? Doubt it.

Leave a comment