My grandpa was a force. Big laugh, booming voice, handshake like a vice, even into his old age. My dad, the “underground village chief,” got his charm straight from him—schmoozing was in the blood. Grandpa grew up in a little mountain-edge village, a speck of homes hugging the wild.

He had a younger brother nobody talks about—never met him myself. They were opposites, like night and day. Grandpa was the loud one, all action; his brother was soft-spoken, bookish. My great-grandma—Ah Zu—said they balanced each other perfectly. Village folks agreed: one warrior, one scholar, two sides of a coin.

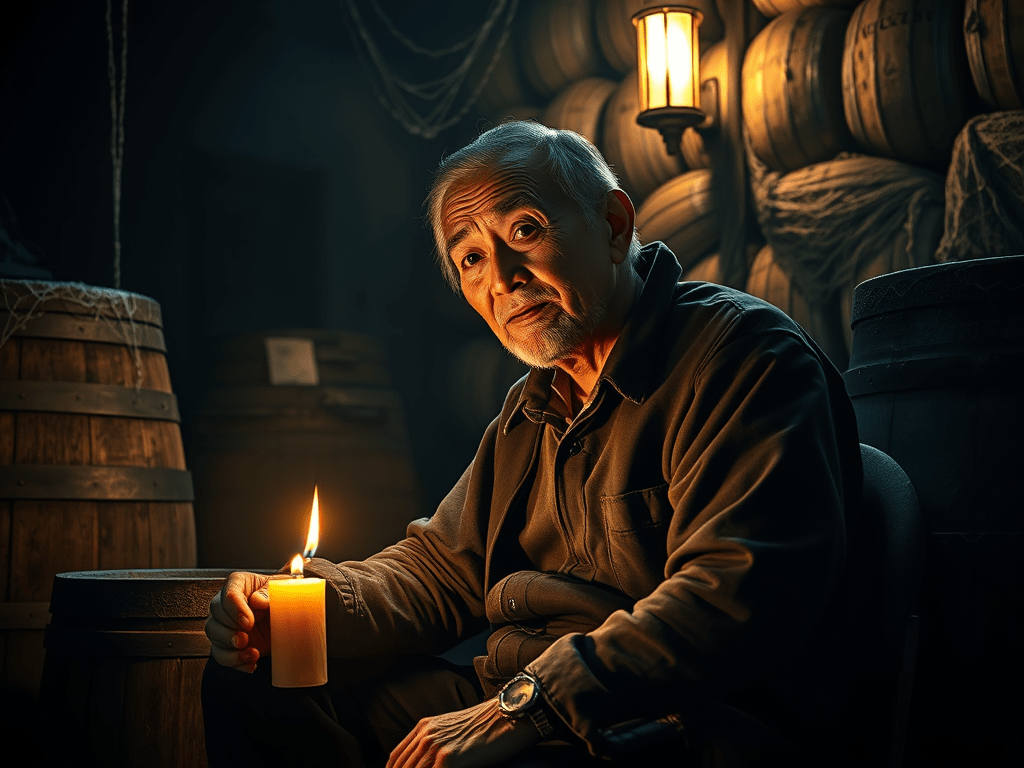

Back then, spring meant bamboo shoots. They’d sprout fast, and if you didn’t snag them quick, they’d turn bitter. So, at 3 a.m.—dead of sleep—Ah Zu would rouse the boys for the mountain. Pitch-dark trails, baskets in hand, chasing the harvest.

Living by the mountain, you couldn’t escape the tales. Mo-gin-za—mountain spirits—weren’t gods or ghosts, but something in between. Mischievous little bastards, lower than deities, kinder than ghouls. Loved pranks—luring folks astray, giggling as villagers scrambled to find them. Rarely hurt anyone, just stuffed their mouths with dirt for laughs. When someone got “led away,” their family freaked, but the village stayed calm—odds were good they’d come back, muddy and sheepish.

It was a scorching summer day when Grandpa and his brother hit the stream to cool off. On the way back, they poked around, picking up pebbles. Then they spotted it—a hat, abandoned, cute enough for kids to covet. They took turns wearing it, goofing off all the way home.

That’s when the shift hit. Grandpa’s brother turned strange. Eyes wide, always watching, hat glued to his head. Quiet kid went hyper—jumping, slamming tables, making weird noises. In midnight, he’d bolt outside, crowing like a rooster to wake the village.

Wild, worrying wild. Neighbors started whispering, “Something’s off with your little guy.”

Grandpa and the family were skeptics—kids being lively was fine, right? But this? Too much. They planned to haul him to a famed exorcist in the next village the following morning.

That night, he vanished. Grandpa’s mom found out at dawn—sobbing, frantic. The village rallied—searched sheds, coops, fields, every corner, sane or not. Nothing.

A neighbor fetched the exorcist. By dusk, he arrived, heard the tale, and said one line: “The hat’s the problem—Mo-gin-za’s taken him. Look in the mountains.”

“Spirits with soul—gods, ghosts, whatever—can latch onto beasts or men, no difference.” From then on, pre-dawn, the village gathered—drums, gongs, shouting, “Little guy, come out!” Day after day, up the slopes—nothing.

A week in, they found him. Grandpa’s brother, still as stone, lay in a mountain gully. Hat gone, back to his old quiet self—just not breathing.

Years later, when the village had moved on, Grandpa hadn’t. He carried it close.

That day by the stream, he’d spotted the hat first, wanted it for himself. But his shy little brother piped up, “Big Bro, it’s so cool—can I wear it?”

Leave a comment